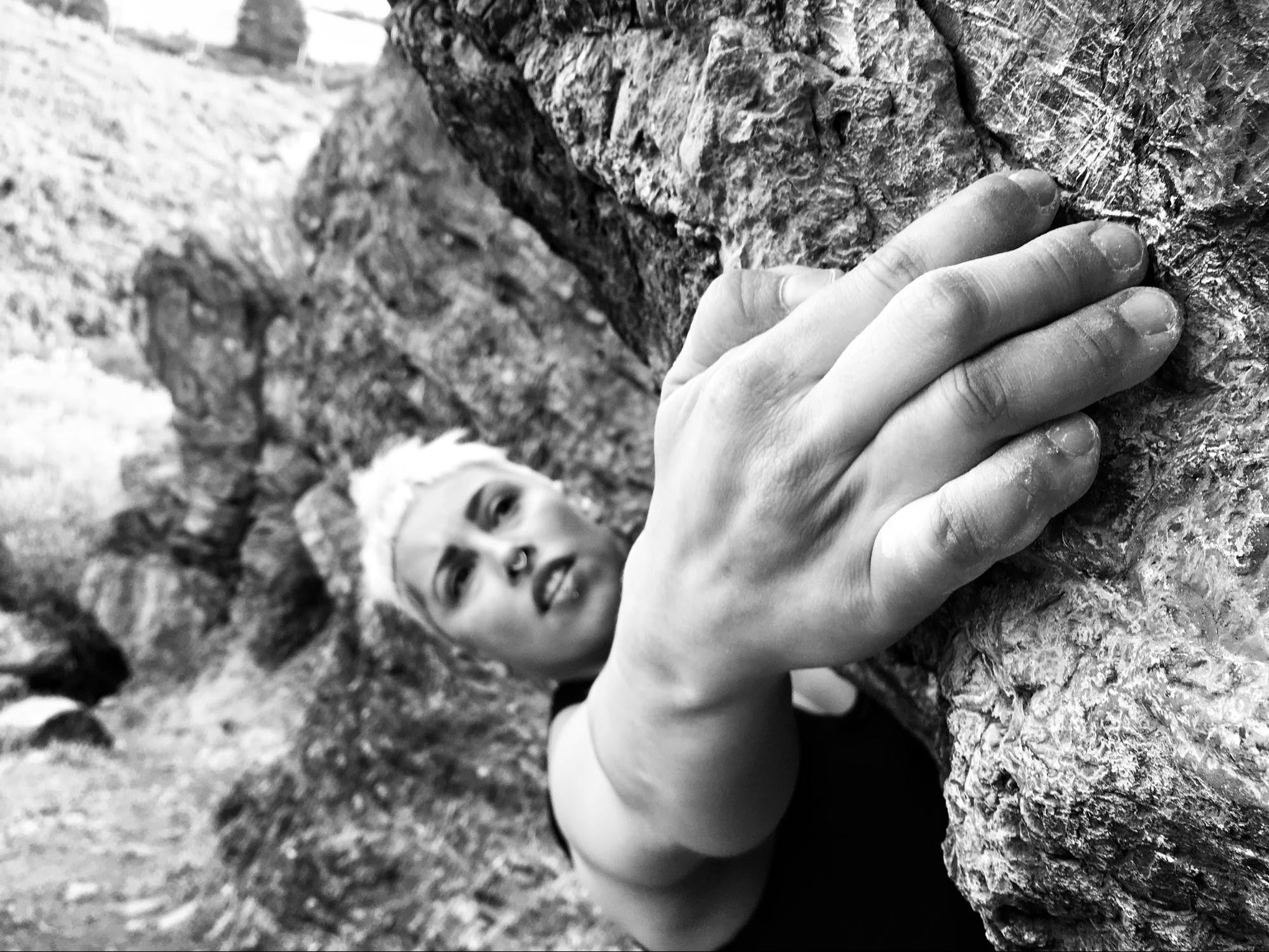

Dr. Natasha Barnes is a trailblazer. From bouldering before it was cool to busting out 355 lb deadlifts to crimping harder than most of the boys to starring in climbing videos to winning an ABS National Championship to earning her doctorate as a chiropractor—Tash has always followed her passions on her own terms. Prepare to get inspired by Tash's strength—both physical and mental—and read up on her pro tips for stretching, training, building strength, and recovery in our interview below.

How did you get into climbing?

My dad took me to the climbing gym for the first time. They were hosting a climbing competition one of the weekends we were there, and I competed and won at age 11! I was hooked. Unfortunately, I stopped climbing for a few years, but when I got into high school I met a friend, Jonathan Wright, who also climbed. He had a car so we would go Thursdays after school. That soon went from a one day a week thing to an everyday thing as we both got hooked!

What do you enjoy most about working with fellow climbers in your sports medicine practice?

Understanding where climbers are coming from. I’ve been there after several of my own injuries. It can be a really frustrating and demoralizing thing to be injured. Having someone who understands your sport and understands the lingo can be such a relief and provide a lot of hope. I like being there for my fellow climbers. Plus, climbing is an amazing sport and it’s really fun to help some of the most amazing and most motivated athletes in the world perform at their peak even when they aren’t injured.

After your finger injury in 2005, how did you cope with not being able to climb for 6+ months? How did you ease back into climbing after that, and did the injury change the way you approach the sport?

It was hard to cope. I was a pretty bad A2 pulley injury. I had no idea how to fix it and neither did anyone else it seemed. I got really depressed because climbing was my identity. I thought resting until it didn’t hurt was the best way to approach it, but it wasn’t working. I did 30 days in a row of Bikram yoga, tried out cycling, went to the gym and did heaps and heaps of cardio—nothing could fill the void. I wish I would have known about strength training and weightlifting back then. It would have been a good way to keep my body strong while my injury healed.

Eventually, I decided to push my boundaries. I went on a climbing trip to Lost Rock where there were no names or grades—just a lot of fun bouldering on great rock on a beautiful beach with a redwood forest backdrop. In the past I had really only cared about climbing as hard as possible, competitions, and sending hard boulders even if it meant they were not very fun to climb. This time I started to appreciate other things about climbing. The scenery, the enjoyment of actually moving on rock, the texture of the rock, the moments with friends, etc. I started to really appreciate climbing in a totally different way.

I climbed on some crimpy edges and felt like I was potentially injuring my finger more. But then something interesting happened... it actually started healing. I realized that you have to MAKE something heal, not WAIT for it to heal. Taking time off initially was smart but I needed to be rehabbing. That was one of the biggest motivators for me to go to school to learn sports medicine. So that I could help other people the way I wish I had been helped.

The A2 is one of the most common climbing injuries it seems. It sounds like you’re saying rest followed by some reintroduction is ideal. Can you give more details around that? What specific techniques have you seen be effective for this injury?

Tissues respond to load and after a certain point if you don’t start reintroducing load to the injured tissue in an incremental way it won’t heal properly. Initially, you need to rest for the the first week or so after the injury (longer depending on the severity) so that the inflammation can settle down, after that you have to start the rehab process and you have to start gradually loading the tissue if you want it to heal properly.

What I recommend to my athletes is to start climbing on good holds open handed on low angled walls. Top rope is usually ideal because routes tend to be much easier than bouldering and lower impact on the body. After that athletes can progress to two handed hangs on the hangboard on large edges with weight taken off using a pulley system or bands, then to hangs with less weight taken off, then to body weight hangs and finally progressing to weighted hangs. Usually, around the time that athletes are back to body weight hangs we can start slowly introducing normal climbing back into the mix. By the time they are doing weighted hangs, it’s more of a pre-training phase where they are pretty much back to normal but doing some “pre-hab” to prevent future injury.

A little bit of self-massage using an acupressure ring, guasha/graston tool or even a spoon can be helpful but should not be over-done. Err on the side of doing too little. It feels good and it is very easy to cross the line from helpful to causing actual tissue damage.

The timeframe of all of these steps is completely dependent on the athlete, severity of injury, ability of the athlete to follow strict guidelines and not do too much too soon, the training age of the athlete, and how long they have been climbing beforehand.

The caveat to all of this:

- NEVER go higher than a 2-3/10 on the pain scale (0= no pain 10=worst pain you’ve ever had)

- If it’s sore or swollen 24 hours later you overdid it. Take 2-3 days off and ice (for the first 24-48 hours) and start the process over again.

- A little discomfort is to be expected but there should never be frank pain during rehab.

- Progress slower than you want to! Climbing isn’t going anywhere and the new set at the gym or that trip your friends are going on isn’t worth chronic injury.

How do climbing injuries differ from injuries incurred from other sports?

Climbing produces some unique biomechanical forces to the body in ways that a lot of other sports do not. This can affect the severity and types of injures that climbers get. For example, It’s important to understand how a heel hook can strain a calf or tear a meniscus and why and also be able to teach people how to do these things properly so they don’t go out and do it again. Only a climber can really understand these things.

What is the most common mistake people make when heel hooking? How can they do it correctly?

The most common mistake I see when people are heel hooking is that they don’t engage their entire leg musculature, glutes and trunk muscles (aka core). They just throw their heel up there and hang on their hamstring. A heel hook is a full body technique and if you’re not doing that way you need to be taught by a professional coach and you need to practice it a lot!

Watch climbers like Alex Puccio, Emily Harrington, Lynn Hill, Nina Williams, Lisa Rands, and Robyn Erbesfield Raboutou, just to name a few. These athletes are strong and have excellent technique, which matters a whole lot more when you are 5’2”-5’4”.

Tell us about your pre-climb ritual, including any steps you take to prevent injuries.

I am a huge believer of self-myofascial release. Using lacrosse balls and foam rollers, you can work on tight tissue that could potentially become problematic. I do this before climbing and on rest days to stay healthy.

This is a question we’ve seen come up before: does it compromise your ability to perform athletically if you do myofascial release immediately before or during climbing? Some people think it’s best to only do it after or during rest, not immediately before or during. Thoughts?

There is an issue with doing too much rolling before climbing or training and traumatizing your muscles and nervous system. If you smash your muscles too hard before climbing, it can affect your performance.

What I tell my athletes to do is spend one minute doing release work on any area that might prevent them from getting into optimal positions for climbing and save the rest for after or for a rest day. For example, If you know you have tight shoulders and it’s going to cause a problem during climbing because your overhead range of motion is limited, then make sure to roll your lats, teres, infraspinatus, and levator scapulae for about a minute each before you climb. Or if you know your hips are tight and your turnout is limited, be sure to roll your glutes and piriformis out for about one minute on each side before you climb.

If your positions suck, your climbing will, too. You have to spend a little time before climbing preparing your body to move better.

As an aside, I wouldn’t waste time stretching. Most people need tissue work—NOT stretching—and I guarantee you’ll get more out of rolling if you do it properly. Here is my advice. If you must stretch because it makes you feel better, then save it for after climbing or training or for rest days.

I’m also a firm believer in strength training. The stronger you can make your body, the more resistant you’ll be to injury. Especially since climbing is a lot of pulling and not a whole lot of pushing and people tend to develop huge imbalances. It’s important to train your entire body to be more functional. The compound barbell movements such as the squat, overhead press, bench press and deadlift are some of my favorites to train. Particularly because they utilize the full kinetic chain over the longest most effective range of motion that allows the most weight to be used. And progress is exactly measurable down to the 1/4lb.

What’s your climbing routine like now? How many days a week do you climb, and what type of climbing do you do?

Recently, I haven’t been doing any climbing. Just strength training and hangboarding. I have some goals for powerlifting that I’d like to accomplish first. I plan to get back to climbing in the fall. My coach and I have some plans to use a program called Texas Method that is used for strength training and translate it into a climbing program as an experiment. I think it’s going to work out really well!

What’s unique about Texas Method and what makes you so hopeful for its climbing adaptation?

Texas Method is an intermediate program that takes into consideration an athlete’s ability to recover from the stress applied during training. Technically speaking, what makes an athlete a novice, intermediate, or advanced isn’t whether they climb V1/V4/V8/V12—it’s the time needed to recover from training stress. A novice will recover in 24-48 hours and another stress can be applied, an intermediate athlete will need about a week to recover from a large stress like a hard climbing session before another large stress can be applied. Texas Method takes this into account. The program would look something like this:

Day 1

Volume day (5x5 or something similar)

Day 2

Recovery day (light day climbing at about 80%)

Day 3

Intensity day (short hard climbing session climbing 5 hard climbs or something similar)

Variations can be programmed such as a four day week but this would be the gist of it. This way overreaching and overtraining doesn't happen and progress doesn't stall. I'm sure there would be other tweaks to be made, as we haven't experimented with it yet, but I think this would be the general format.

I believe climbing coach Rob Miller is using Texas Method with his athletes already with great success.

How do you balance your sports medicine practice, climbing, and find time to relax?

I put boundaries on how much I will work. Work to live, not live to work is a motto I hold myself to. Rest time and training time are sacred to me and I’d rather give up the luxury of other things than give up my free time. The first job I had out of school was in a large practice that burned me out to the point of wanting to change careers. I nearly went back to route setting! I’ll never do that again.

What was your “aha!” moment with FrictionLabs?

I ordered the free sample and was hooked immediately! I noticed that the chalk stuck to my hands even after climbing a couple warmups and when I tested it on the ultimate rock, Yosemite granite, I knew I couldn’t go back. The difference is immediately noticeable.

What are the most common injuries you see among climbers?

Finger, shoulder and elbow injuries!

What’s a misconception you’ve heard about treating climbing-related injuries?

Climbers are really motivated and often times they try and diagnose and fix themselves. Climbing injuries aren’t always what they seem though. What is presenting as an elbow issue can sometimes be nerve impingement in the neck, what looks and feels like a rotator cuff sprain can actually be a SLAP tear that is surgical or simply a biceps tendonitis caused by impingement and the treatments are drastically different. It’s always a good idea to at least get a proper diagnosis so you know what you are dealing with before attempting any rehab or treatment. Otherwise you could be barking up the wrong tree or worse, the injury could go from treatable with soft tissue work and rehab to chronic and surgical. The more time you waste trying to Google symptoms and self treat the more chronic the injury becomes and the more expensive and invasive the treatments start to become too. That’s why people like me spend 4+ years getting graduate degrees on these things, because you can’t learn this stuff properly from Google. Get a professional opinion before you waste any more time!

Natasha shares awesome training trips, stretches, and performance strategy for climbers on her website, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Her business Instagram also has useful and inspiring tips and tricks. Check 'em out!